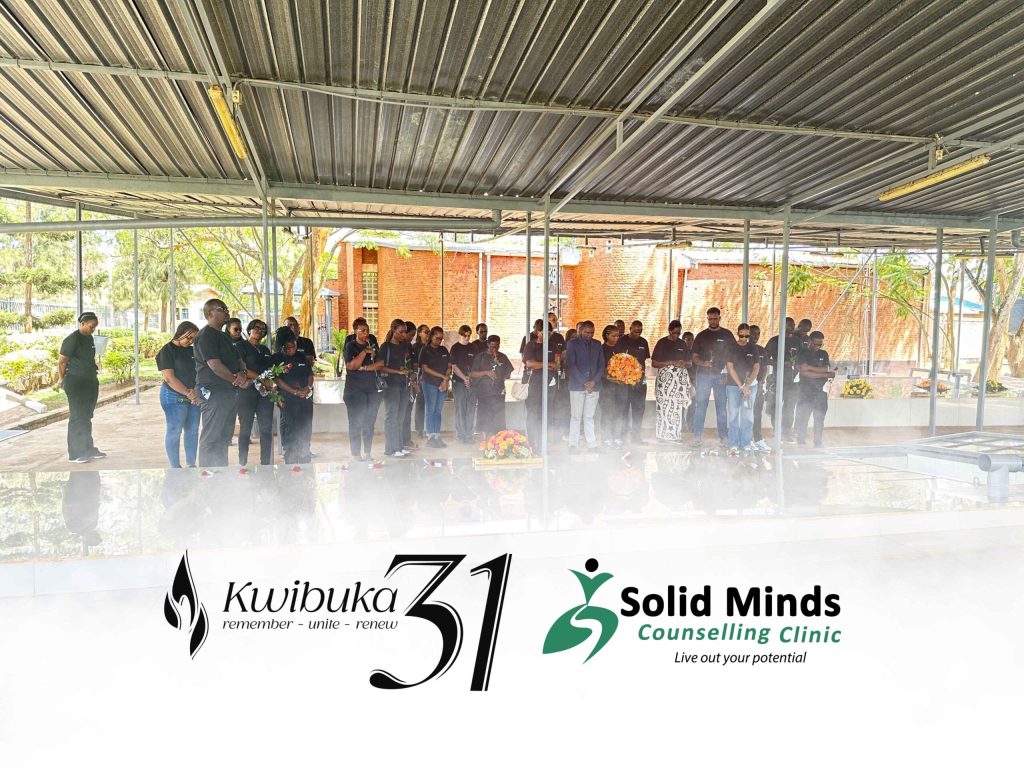

Samuel Munderere Reflects on 31 Years of Remembrance During Solid Minds’ Visit to Nyamata Genocide Memorial

It’s an honour to speak with you today about the Genocide against the Tutsi and the work that I do closely with survivors of the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi men, women, and children whose lives were forever changed in just 100 days of unimaginable violence.

Thirty-one years later, survivors still carry the deep wounds of that trauma. But just as Rwanda has rebuilt itself over the last three decades, so too have survivors had to rebuild not only their lives, but also their sense of dignity, community, and hope.

The Early Years – Emergency Support and Survival (1994–2005)

In the immediate aftermath of the genocide, the needs of survivors were urgent and overwhelming:

- Basic survival – food, shelter, and medical attention were priorities. Many survivors had lost everything.

- Security and protection – survivors feared continued violence and reprisal.

- Justice and accountability – through Gacaca courts and the formal justice system, many sought closure and recognition of what they had endured.

In these years, our work centered on emergency response offering trauma care, housing, and basic services in whatever form was possible.

Rebuilding Lives – Recovery and Integration (2006–2016)

As the country began to stabilize, the focus shifted toward long-term recovery and reintegration. Mental health care became increasingly vital as trauma, depression, and PTSD surfaced more visibly. Economic empowerment was critical for dignity and sustainability especially for widows, orphans, and women who had survived sexual violence. Community-building became a healing tool. We began forming community groups, survivor networks, and peer support models to break isolation and foster belonging.

These efforts helped survivors move from merely surviving to starting to live again, with agency and renewed purpose.

Victims of Sexual Violence and Children Born of the Genocide

Among the most brutal and painful aspects of the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi was the widespread and systematic use of sexual violence as weapon of war.

An estimated 250,000 women and girls were raped, tortured, and enslaved, often in public and horrifying ways. For many, the physical wounds healed over time but the emotional, psychological, and social scars remain deep and enduring.

Some of these women became pregnant from rape, and many gave birth to children in the aftermath of the genocide children often referred to as Children of Bad Memory or Children of the Killers who are now 30 or 31 years old. These children, born of unimaginable violence, are a living legacy of trauma. They represent a unique, group in Rwanda’s recovery story.

The Mothers

For the mothers, the journey has been filled with pain and silence.

- Many hid their pregnancies out of fear of shame, stigma, or rejection.

- Others were rejected by their families or communities, seen as reminders of the violence or wrongly blamed for their victimhood.

- Some struggled to bond with their children, feeling torn between love and trauma.

Despite this, many of these women demonstrated incredible strength and raised their children with deep care and sacrifice often in isolation and poverty, and with little formal support until recent years.

At Survivors Fund and other survivor-focused organizations, we have worked closely with many of these women helping them process their trauma, reconnect with their identity, and rebuild their sense of self-worth through support groups, and economic empowerment.

The Children Born of Rape

Now adults, many of these children have grown up with complex identities and emotional struggles:

- Some learned later in life about the circumstances of their birth, triggering feelings of rejection, shame, or confusion about who they are.

- Others have faced stigma from communities or even family, treated as if they carry the guilt of their biological fathers.

- A number of these young people experience mental health challenges, including depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts often in silence, without access to support.

Their pain is invisible to many, and yet it runs deep. They are secondary survivors, carrying the inherited trauma of genocide and the weight of a history they did not choose.

But many are also resilient, intelligent, and determined to live meaningful lives. With the right support education, mentorship, and community belonging they are breaking cycles of trauma and becoming powerful voices for healing and change in Rwanda. At SURF we have supported 830 such youth attain education.

Supporting these mothers and children/youth is not only about justice; it’s about restoring dignity, creating pathways to healing, and ensuring that no one is forgotten

Today’s Realities – Aging, Isolation, and a New Generation (2017–Present)

Today, 31 years on, the needs of survivors are again evolving.

- Aging and chronic illness: Many survivors are now elderly and live with age-related health issues, made worse by trauma, poverty, and a lifetime of hardship. Access to specialized care is limited.

- Housing and dignity: Some survivors still live in precarious or inadequate housing, a daily reminder of the instability they’ve endured.

- Intergenerational trauma: Children born of rape during the genocide and second-generation survivors face deep identity challenges, stigma, and mental health needs. They often carry pain that was never directly theirs.

- Mental health concerns remain a serious barrier. Despite progress, many still suffer in silence. This is why our toll-free counselling lines and community-based mental health groups are so critical they bring care directly to where survivors are.

The Ongoing Challenge

Even with everything Rwanda has achieved, survivors continue to live with layered vulnerability economic, emotional, and social. Many still feel left behind, especially as the world’s attention moves on.

We must ask ourselves at individual level, How do we contribute to ensuring survivors live with dignity? How do we build systems that acknowledge long-term trauma not just in words, but in action?

In conclusion, Let’s look at Survivors of the genocide not as victims of the past they are architects of Rwanda’s future. They are teachers, parents, leaders, and role models. Their strength is a testament to the spirit of Rwanda.

Let us remember them not just once a year, but every day, through the actions we take and the dignity we uphold.